When A’s Stop Meaning “Prepared”

How Grade Inflation in CA High Schools Is Leaving Students Unready for College Math

The Problem

In November, UC San Diego released an admissions report that drew national attention for an unsettling finding: a growing share of admitted students lack basic math skills. In Fall 2025, 11.8% of first-year UCSD students placed into remedial math courses covering middle- and high-school–level material, up from just 0.5% in Fall 2020. To put this into perspective, UCSD gave a test to 138 students in their remedial Math 2 course, and 25% were unable to solve the equation 7 + 2 = _ + 6.

Unsurprisingly, commentators across mainstream media rushed to explain the trend. In academic conversations I have been part of, people point to test-optional policies, COVID-related learning loss, generative AI, and increased enrollment from under-resourced high schools. While each of these factors likely plays a role, one major contributor has received far less scrutiny: grade inflation driven by declining academic standards in California public schools.

The New York Times and Wall Street Journal often publish articles highlighting grade inflation at elite universities like Harvard and Yale. However, the same phenomenon is going mostly unnoticed in California public high schools. The UCSD report offers a rare look at some of the downstream consequences.

Brief Aside & Framing

I attended San Diego Unified schools for the entirety of my K-12 education. I am proud of the education I received: I had many wonderful teachers and felt well-prepared entering college. Precisely because of this experience, I feel compelled to raise concerns about whether today’s students are being set up for the same level of success.

Grade inflation is a battle on two fronts: failing students advancing to the next grade and the achievements of high-performing students being diluted. Here, we focus on the latter.

This piece focuses primarily on San Diego Unified School District (SDUSD), not to single it out for criticism, but because it is UCSD’s largest local feeder district and serves as a useful case study for broader trends across California1.

The Evidence

The year 2020 brought sweeping changes to education. Amid the nationwide disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, one shift received far less attention than it deserved: SDUSD’s move from a “traditional” grading system to a “standards-based” mastery grading system. Under standards-based grading, students can retake assessments and resubmit assignments throughout the year. Research suggests that in mastery-graded courses, it can be easier for students to earn higher grades.

At the same time, AP exams have gradually become less demanding, and standardized tests like the SAT and ACT are no longer used in UC admissions. This means high school grades now carry more weight than ever as signals of academic readiness, making their inflation especially consequential.

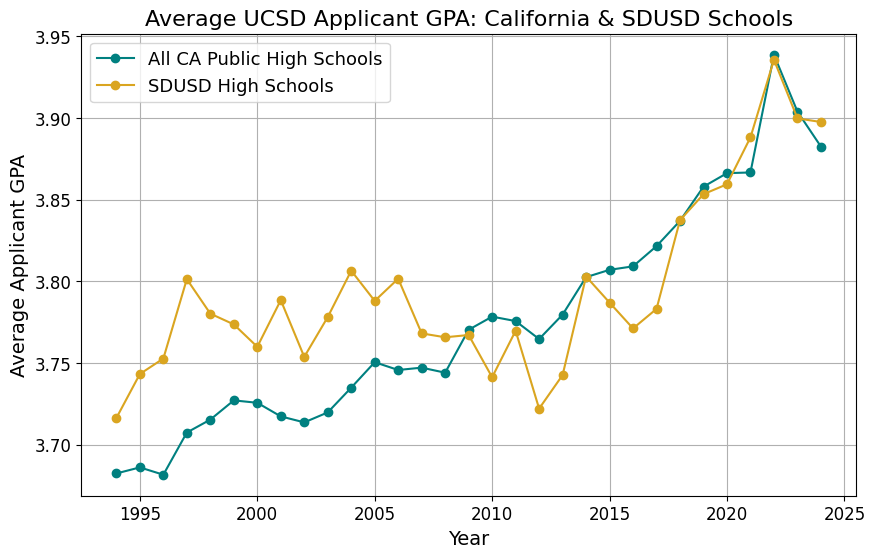

UCSD’s report explicitly acknowledges this issue, noting “a mismatch between students’ course level/grades and their actual levels of preparation.” Specifically, the report finds that, in 2024, students placed into remedial math had a higher average high school math GPA than students who placed into Math 3C—the earliest non-remedial math course—in 2019. The authors largely attribute this to UC initiatives, beginning in 2016, aimed at expanding recruitment from LCFF+ schools—California public schools where over 75% of students qualify as low-income, English learners, or foster youth. If this were the primary driver, we would expect average applicant GPAs to decline. Instead, applicant GPAs have risen steadily. According to publicly available UCSD admissions data, among applicants from California public schools, the average GPA has increased year after year; in SDUSD alone, it rose from 3.77 in 2016 to 3.94 in 20222.

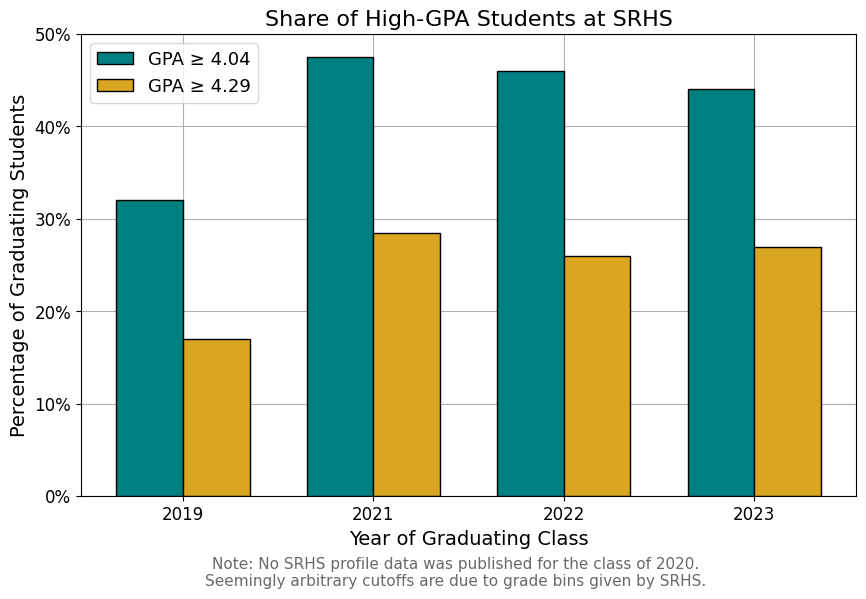

Further evidence comes from SDUSD “school profiles”. Four SDUSD high schools—Clairemont, La Jolla, Mira Mesa, and Scripps Ranch—publish annual profiles detailing courses offered, student demographics, and academic performance, including the GPA distribution of the most recent graduating class. Clairemont and La Jolla high publish distributions too coarse to analyze (the top bin is 3.5+), leaving the profiles from Mira Mesa and Scripps Ranch for us to inspect.

At Mira Mesa High School, 23% of the class of 2019 attained a 4.0 GPA or higher. Among the next available cohort, the class of 2023, this share rose to 30%. The shift is even more pronounced at Scripps Ranch High School (my alma mater). After 2019—the last year of traditional grading—the share of students graduating with a GPA of 4.04 or higher rose from 32% to 48% (a 16-percentage-point increase, or a 48% relative increase), while the share with a GPA of 4.29 or higher rose from 16% to 28% (a 12-percentage-point increase, or a 68% relative increase).

I want to be clear that I am not solely blaming standards-based grading for this grade inflation. I think it is likely that the true cause is multifaceted. However, I do think that there is a prevailing notion that grade inflation is simply due to schools giving students a little bit of grace during the COVID-19 pandemic. I do not believe this to be the case—the UCSD matriculating class of 2025 would not have entered high school until Fall 2021, after SDUSD had resumed in-person instruction. I believe that pointing to concrete education policy changes, such as standards-based grading, shifts the conversation toward actionable reforms, rather than waiting for COVID learning loss to dissipate.

Why This Matters

At this point, I have hopefully convinced you that grade inflation is occurring in California high schools. The natural question is: why does this matter? After all, higher grades might seem like an unambiguous benefit for students. In reality, grade inflation carries serious downstream consequences—especially for the very students it is often intended to help.

I group these concerns into two categories: (1) objective issues raised by UC San Diego’s own report, and (2) broader, more subjective concerns about long-term impacts.

Report-Based Objective Concerns

UC San Diego’s Proposed Solution Risks Harming Disadvantaged Students

On page 34 of the report, the authors recommend creating a “Math Index” to address poor math preparedness. This index is intended to serve as UCSD’s “best predictor for how a given applicant would perform on the math placement exam once admitted,” and would be applied to future applicants during admissions review.

Crucially, one component of the Math Index is the applicant’s high school. Anticipating concerns, the authors argue that because remedial math placement varies systematically by high school—even after controlling for transcript information—it is “essential” to include a high school indicator in the model.

To see the problem, consider two equally strong students. Both earn straight A’s in math, completing the same coursework (e.g. AP Calculus AB). However, Student A attends La Jolla High, a well-performing school in a wealthy area, while Student B attends Lincoln High, a lower-performing school that serves traditionally working-class students. This will result in Student A, who is likely from a much higher socioeconomic status than Student B, having a higher Math Index and thus a more favorable application.

I do not believe the authors intend to disadvantage low-socioeconomic-status students. Rather, they are attempting to compensate for distorted academic signals in the data they receive. But this highlights the real culprit: high schools inflating the grades of their students, in turn potentially causing some of their high-performing students to face an even steeper uphill battle.

UCSD’s Report Attributes Blame to Increasing the Proportion of In-State Students

The report offers three explanations for rising math unpreparedness. The first—expanded enrollment from LCFF+ high schools—was expected and has already been discussed. The second, however, gave me major pause: an “increase in the proportion of in-state students”.

Beginning in 2022, the UC Office of the President directed UC San Diego to increase enrollment of California residents. The report suggests this shift may help explain declining math preparedness. While the report does not provide information comparing the number of in-state and out-of-state students requiring remedial math (which would be extremely valuable), the mere framing is concerning.

If it is true that admitting more California public school students plausibly explains weaker math outcomes, it should alarm anyone invested in the state’s education system. However, I do feel the need to point out that the UCSD report does not adequately support this claim with data.

Personal Subjective Concerns

Grade Inflation Hurts Disadvantaged Students in College Admissions

The previous section focused on comparisons across schools. But grade inflation may harm disadvantaged students even more within the same school.

Consider two students attending the same high school. Student A is academically stronger than Student B, but because grades are inflated, both earn similarly high GPAs. With grades providing little signal—and standardized tests unavailable—colleges turn to extracurriculars. Student B, from an upper-middle-class family, can afford a fancy-looking unpaid internship. Student A works a fast-food job to help support their family. Which extracurricular do you think will be viewed more favorably for college preparedness by an admissions committee? My bet is on the unpaid internship.

Lack of Math Preparedness Could Cause an Exodus of Students from Urban Districts

Perhaps you are not concerned with students who are performing well enough to potentially gain entry to prestigious colleges like UCSD. After all, these students represent a minority of our public school system. However, the issue of grade inflation still impacts all students.

If families perceive that urban districts like SDUSD are not adequately preparing students for college-level coursework, those with means may seek alternatives, such as private schools or transfers to higher-performing suburban districts (e.g. Poway Unified). District funding depends on enrollment, and thus a potential exodus of students from urban districts would dry up funding, leaving fewer resources to support the students who need them most.

Discussion, Conclusion, and Potential Solutions

I am not going to pretend to have a solution to the problem put forth here. Restoring meaningful academic signals in California public education will require a coordinated effort across high schools, districts, universities, and policymakers, and any serious reform will inevitably involve tradeoffs. That said, acknowledging the complexity of the problem should not prevent us from taking concrete steps. I will wrap up this post with a couple of ideas to get some momentum going towards solving this problem.

On page 40 of their report, UCSD mentions reaching out to local high schools (*cough cough, SDUSD*) to privately tell them if the math preparation of their graduates is not consistent with the transcripts they have received. This is a great idea, and would give the high schools a valuable (and rare) source of feedback on how their students fare after they depart for greener pastures. I might even suggest making this information publicly available, to ensure schools are held responsible for the performance of their students.

As a whole, I would also like to see more publicly available data from high schools on their grades. It took me hours of searching the web (and using the internet archive) to find basic information about grade distributions at just a handful of high schools. I appreciate that UCSD has an easy-to-use public-facing database with all of their aggregated admissions data, including GPAs by high school. It would be much easier to hold schools accountable if a publicly-available database of high school grade distributions over time existed.

San Diego Unified is the second largest school district in California.